Tales from the Trenches

Editor’s Note: This issue features the Conference of California Bar Associations (CCBA). It should not be confused with the Contra Costa County Bar Association (CCCBA).

I first attended the annual Conference of California Conference of Bar Associations (CCBA) in 2006, as a delegate from the Bar Association of San Francisco. Since then, I have chaired the BASF Delegation, served on the CCBA Resolutions Committee, and have been to every statewide Conference since 2008. For me, the Conference is a richly rewarding opportunity to affect public policy. You always meet prominent and interesting lawyers from around the state and learn from them.

Each year, approximately 50 to 60 resolutions are debated during the two-day Conference, so time is limited. Delegates who want to speak have to learn to state their case in two or three minutes, with another minute for rebuttal. I find that it’s tougher than being in court! And it’s fantastic training for young lawyers!

Involvement can develop your relationships within your local bar association and help you make professional connections throughout California. It has costs in time and money, for sure, because all the participants are volunteers. But it pays for itself, either in business connections or in personal satisfaction, or both. Although no Continuing Legal Education (CLE) credits are offered for the Conference, many local associations, including the Contra Costa County Bar Association offer CLE for participation in the delegation’s study group meetings done in preparation for the Conference.

My CCBA and Conference experience includes authoring a resolution that has become law. In my practice as a trusts and estates litigator, I was troubled by the 2011 decision of Estate of Bartsch (2011) 193 Cal.App.4th 885. As a part of the probate of a will the beneficiaries must be determined as well as their distribution rights. This proceeding may be initiated by the personal representative or by any person claiming to be a beneficiary. Personal representatives are not considered true adversaries in the proceedings and have a duty to be fair to all those interested in the estate, even if they are also beneficiaries or heirs. (See Bodine v. Superior Court (1962) 209 Cal.App.2d 354, 360.) In Estate of Bartsch, the appellate court held that since the personal representative is assisting the court he or she may participate fully in the litigation and be entitled to have their litigation fees paid by the estate, even if in doing so they are promoting their own interests as a beneficiary and not solely acting in their neutral role as personal representative. (Estate of Bartsch (2011) 193 Cal.App.4th 885, 900.) In so doing, the court made the Probate Code section in question applicable in situations where experienced practitioners had never imagined the statute would apply. The court explained that, although the legislative history revealed that the legislature may have intended the statute to apply to only a specific situation, the language in the statute must be construed as applying to other situations as well. This created a situation in which the fiduciary who administered an estate could engage in self-dealing by taking sides in a dispute in which he or she also had a personal interest.

Fixing this anomaly required new legislation. I crafted a resolution that would amend the law addressed in Estate of Bartsch. The resolution needed to be carefully drafted, to assure that the resolution would resolve the self-dealing concerns without having unintended consequences. I prepared a resolution, got BASF to approve it, and presented it to the CCBA. By the time of the annual Conference, many other delegations had taken positions against the resolution. Given the technical nature of probate litigation procedure, only a small portion of the delegates cared about, much less understood, the resolution. The executive committee of the State Bar of California’s Trusts and Estates Section agreed that legislation was needed to address the Estate of Bartsch decision, but felt the resolution was not the proper solution. I began the exciting, but challenging, task of educating delegates and changing their positions. The give and take that occurs at the Conference has some of the flavor of an old-style political convention: larger delegations have hospitality suites and caucus rooms, and there is constant lobbying and cajoling to get delegations to change their positions. I worked with another delegation to propose a friendly amendment with new language. Then, I lobbied the Conference Calendar Coordinating Committee to get my resolution rescheduled for a later debate, to give me more time to change minds. That year, the Conference was on the Queen Mary in Long Beach. I vividly remember hustling from ballroom to ballroom on that enormous old liner in order to address members of the larger bar associations as they met for cocktails, breakfasts, and lunches. The resolution passed, but it was a close vote.

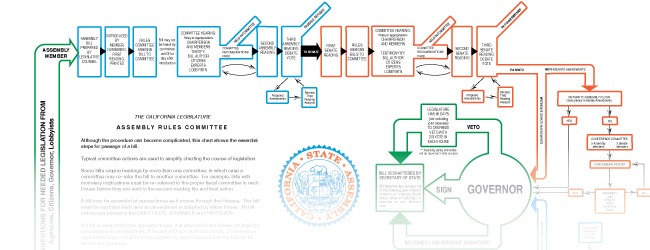

The next steps took a lot of my attention for a while, especially during the legislature’s session. The CCBA lobbyist, Larry Doyle, persuaded Assemblyman Don Wagner, an attorney, to sponsor the bill. Before any legislative votes were taken, however, Larry and I had numerous meetings with legislative staffers, representatives of the Judicial Council, the California Judges Association, the relevant state bar executive committee, and the judiciary committees of the two houses. Through this lobbying effort, I learned that committee staffers, even very junior ones, have great power, and can easily kill a bill for any of a variety of reasons. The hard work resulted in a bill that was signed into law by Governor Jerry Brown in September 2013, which became law as of January 1, 2014.

My advice to attorneys considering involvement in the Conference? Do it. You will not regret it. Delegates study, debate, and vote on resolutions proposing changes in the law first at the local delegation level and then again at the statewide annual conference level. Any delegate can write a resolution that might become law. I would suggest that for the first year or two you just watch and enjoy yourself until you learn the ropes. But then start writing resolutions. That is what really draws you in. But I would never do this were it not also fun. I always say that just practicing law all day would drive me nuts—I need activities like this for my sanity, to prevent burnout, and to maintain an interest in the legal system.